Most AngularJS developers are probably familiar with the concept of HTTP interceptors: a mechanism for modifying request and responses. This feature is commonly used for cross-cutting concerns such as authentication, logging and error handling.

When Angular 2 was introduced it became clear there (initially) would be no equivalent for HTTP interceptors. In order to support similar functionality in Angular 2 you had to create your own HTTP service which took care of intercepting the request and responses.

While that approach worked fine, it was not a very convenient one. Alternatively, you could have used a third party Angular library to bring back HTTP interceptor support.

With the release of Angular 4.3 the new HttpClient was introduced, which deprecated the Http service. Apart from a much improved API the new HTTP client also brought back the beloved HTTP interceptors. So, everything is good now… right?

The problem with Angular’s HTTP interceptors

While we can be happy about the fact that the interceptors are supported again, I feel like the Angular core team fell into the same trap as in AngularJS: the interceptors are global once more!

Before looking at a (possible) solution, first let’s see what does it mean for an interceptor to be global and why global interceptors can be a problem.

If you take a look at the official documentation for Angular’s HttpClient you’ll find a section called “Intercepting all requests or responses“, that describes how to use HTTP interceptors. Notice that the word all has been highlighted; that is what is meant with global interceptors.

Whenever you define an HTTP interceptor it will intercept all requests and responses. For many applications that presumably is not a problem, however there are enough cases in which this is not desirable.

A common case in which global HTTP interceptors actually become a problem is when your application uses several different and unrelated API’s. These API’s probably require different authentication and error handling. With global interceptors, these interceptors need to be aware that they might possibly intercept messages which they should ignore. For example, if you have created an authentication interceptor for API x, then it is not correct if it also sets an authentication header for requests that target API y.

This is often solved in HTTP interceptors by explicitly checking the URL of the messages to determine which ones should be ignored. Although that works, it is not a very elegant solution as it clutters the interceptor with additional logic. Also, often the exact URLs of the API endpoints are not known in advance (within the interceptor).

Maybe the application is deployed in different environments or the interceptor could be part of an isolated reusable module. In those situations, the URLs are not known in advance and you need to implement a mechanism to provide this information from outside of the interceptor.

Another problem that can occur with global HTTP interceptors is that it can lead to circular dependencies. Recently I encountered such a situation when developing an interceptor that in case of a 401 Unauthorized response would automatically redirect the user to a login screen of a single sign on service.

The interceptor made use of an authentication service, that in turn had a dependency on HttpClient. A simplified dependency graph of the situation is shown below.

Dependency graph diagram

Angular’s HttpClient has a transitive dependency on the HTTP_INTERCEPTORS multi-provider. Since the AutoLoginHttpInterceptor was defined as a global HTTP interceptor (by means of a provider for the HTTP_INTERCEPTORS token), this resulted in a cyclic dependency graph.

The irony of this situation is that the AutoLoginHttpInterceptor should not even have intercepted messages for the AuthenticationService.

Simply checking the URLs of the messages in this case did not help to solve the circular dependency problem. Another solution was needed here.

Non-global HTTP interceptors

Hopefully, by now it is clear why global HTTP interceptors can be a bit of a problem. The obvious solution is to start using non-global / local HTTP interceptors. Although that sounds easy, Angular currently does not offer an easy way to set them up like that.

When starting to look into the problem of how to support non-global interceptors, the goal was to do so without having to introduce a wrapper class for the HttpClient as was needed before Angular 4.3. In the ideal solution services still should have been able to use HttpClient, together with an @Inject decorator as a qualifier to be able to select the right HTTP client.

An example of how this is supposed to look like is shown below:

import { InjectionToken, Inject } from '@angular/core';

import { HttpClient } from '@angular/common/http';

export const HTTP_CLIENT_A = new InjectionToken('HTTP_CLIENT_A');

export const HTTP_CLIENT_B = new InjectionToken('HTTP_CLIENT_B');

export class ServiceA {

constructor(@Inject(HTTP_CLIENT_A) private httpClient: HttpClient) { }

// ...

}

export class ServiceB {

constructor(@Inject(HTTP_CLIENT_B) private httpClient: HttpClient) { }

// ...

}The injection tokens make sure that it is possible to inject different instances of the HttpClient, where each client has its own set of HTTP interceptors. So, the next problem to solve is how to create the different instances of the HttpClient.

The answer can be found by studying the HttpClient constructor, which apparently needs an HttpHandler. By looking at the source of the HttpClientModule we obtain the final piece of the puzzle: how to construct a HttpHandler from a set of HTTP interceptors.

Putting all the pieces together results in a solution that looks like this:

import { Inject, Optional } from '@angular/core';

import {

HTTP_INTERCEPTORS,

HttpBackend,

HttpClient,

HttpEvent,

HttpHandler,

HttpInterceptor,

HttpRequest

} from '@angular/common/http'

import { Observable } from 'rxjs/Observable';

export class HttpClientA extends HttpClient {

constructor(

backend: HttpBackend,

@Optional() @Inject(HTTP_INTERCEPTORS) interceptors: HttpInterceptor[],

localInterceptorX: LocalInterceptorX,

localInterceptorY: LocalInterceptorY

) {

super(interceptingHandler(backend, [...(interceptors || []), localInterceptorX, localInterceptorY]));

}

}

export class HttpClientB extends HttpClient {

constructor(

backend: HttpBackend,

@Optional() @Inject(HTTP_INTERCEPTORS) interceptors: HttpInterceptor[],

localInterceptorZ: LocalInterceptorZ

) {

super(interceptingHandler(backend, [...(interceptors || []), LocalInterceptorZ]));

}

}

// Copied from: https://github.com/angular/angular/blob/5.0.1/packages/common/http/src/module.ts#L28-L35

function interceptingHandler(

backend: HttpBackend, interceptors: HttpInterceptor[] | null = []): HttpHandler {

if (!interceptors) {

return backend;

}

return interceptors.reduceRight(

(next, interceptor) =>;; new HttpInterceptorHandler(next, interceptor), backend);

}

// Copied from: https://github.com/angular/angular/blob/5.0.1/packages/common/http/src/interceptor.ts#L52-L58

class HttpInterceptorHandler implements HttpHandler {

constructor(private next: HttpHandler, private interceptor: HttpInterceptor) {}

handle(req: HttpRequest): Observable {

return this.interceptor.intercept(req, this.next);

}

}Both HTTP clients require an HttpBackend instance, the set of global HTTP interceptors (which might be null) and a number of local interceptors. Together these are passed to the interceptingHandler utility function to construct an HttpHandler, which is used to invoke the super constructor of HttpClient.

Note that the interceptingHandler function and HttpInterceptorHandler class have to be copied from the Angular source code since they are not exported as members from the public API.

Finally, we need to define the providers for these HTTP clients and their injection tokens in a module. An example of how to do so is shown in the code snippet below:

@NgModule({

imports: [ HttpClientModule ],

providers: [

// Local interceptors:

LocalInterceptorX,

LocalInterceptorY,

LocalInterceptorZ,

// HTTP clients:

{ provide: HTTP_CLIENT_A, useClass: HttpClientA },

{ provide: HTTP_CLIENT_B, useClass: HttpClientB }

]

})

export class MyModule { }Together these three code snippets form a working example of how to add non-global HTTP interceptors in an application.

Forking HTTP clients

In the previous section we saw how you could implement non-global HTTP interceptors by creating differently configured HttpClient instances. That approach works well but it is a bit verbose. Also, it lacks the opportunity for creating new HTTP clients by building on top of existing ones.

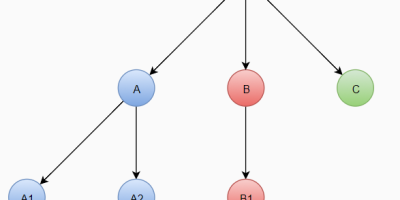

For bigger applications it is not uncommon to use API’s from a number of different vendors. In that scenario we can envision a hierarchical model of HTTP clients. This is illustrated in the diagram below.

Example HTTP client hierarchy diagram

In the diagram above every circle represents an HTTP client. The gray circle is the root / base HTTP client that has only global HTTP interceptors. HTTP clients labeled A, B and C are all used for an API from a different vendor. Those in turn may form the basis for more specific clients as is shown in the diagram for the clients A1, A2 and B1.

In this model each HTTP client (except for the root) is derived from a parent client and they inherit the HTTP interceptors from their parent including a number of additional non-global interceptors.

Given the hierarchical approach outlined above, wouldn’t it be cool if you could tell Angular to simply create a new HTTP client from some parent and add a number of non-global interceptors? Perhaps the code for this could look something like this:

const newHttpClient = someHttpClient.fork(localInterceptor1, localInterceptor2 /* etc... */);Why call this function fork? Well the concept is similar to creating a project fork in VCS systems or doing a process fork in UNIX-based operating systems.

The code example to fork an HTTP client looks simple but unfortunately Angular’s HttpClient has no such function. However, nothing stops you from extending the HttpClient to add it yourself. So that is what I did and therefore created a ForkableHttpClient. The implementation of that class is shown below and it is surprisingly simple.

export class ForkableHttpClient extends HttpClient {

constructor(

@Inject(HttpBackend) private baseHandler: HttpHandler,

@Optional() @Inject(HTTP_INTERCEPTORS) private interceptors: HttpInterceptor[]

) {

super(createInterceptorHandler(baseHandler, interceptors || []));

}

public fork(...interceptors: HttpInterceptor[]): ForkableHttpClient {

return new ForkableHttpClient(this.baseHandler, [...this.interceptors, ...interceptors]);

}

}Basically, all we have to do is keep track of the base HttpHandler and the HttpInterceptor set. With a slightly modified version of the interceptingHandler function a new HttpHandler is created and passed to the HttpClient (super) constructor.

Inside the fork function a new ForkableHttpClient is created by passing the base HttpHandler and the union of the original and additional HTTP interceptor set. Voila; now we’ve got our HTTP client that supports forking!

To make this code easily available for use I created the ngx-forkable-http-client NPM package. This package ships with the ForkableHttpClient class and some additional tools to make it easy to setup the HTTP clients through @NgModule decorator metadata. Documentation and source code can be found at the ngx-forkable-http-client GitHub repository.

Summary

The release of Angular 4.3 brought back the concept of HTTP interceptors, which have been absent since the introduction of Angular 2. HTTP interceptors are commonly used for cross-cutting concerns like error handling, logging and setting the right authentication headers.

Despite the apparent advantages of HTTP interceptors, there are some issues with the way they are currently supported in Angular. The problem lies in the fact that they operate on a global level, meaning that they intercept all HTTP requests and responses.

That might be okay in many cases but it often forces you to add exceptions to ignore certain messages.

It is not uncommon to find an HTTP interceptor that first checks the URL of a message before doing its magic. Although that approach works fine, it sort of pollutes the interceptor with additional logic that is not really related to its core functionality. One could argue that it is violation of the separation of concerns principle.

Another problem with global HTTP interceptors is that they can lead to unexpected circular dependencies that cannot easily be resolved.

These issues can be addressed by switching to non-global HTTP interceptors

Angular offers no out of the box solution for such interceptors. Fortunately, it is not that hard to set them up yourself by introducing multiple HttpClient instances, each configured with a different set of HTTP interceptors. An example of how to do this yourself has been demonstrated in this article.

As an improvement upon the method for creating HTTP client instances with non-global HTTP interceptors a forking approach has been presented that enables the construction of a hierarchy of HTTP clients. Such a hierarchy is useful for applications that use APIs from different vendors and which also have a need for different specialized HTTP clients that target the same API.

To make non-global HTTP interceptors and HTTP client hierarchies easily available I created a small Angular library, which is available as the ngx-forkable-http-client NPM package. Even if you do not need a hierarchy of HTTP clients in your application that library is still useful when you need non-global HTTP interceptors.